BUY, BUY, BONDS

By Rob Sigler, MBA

May 29, 2024

Legendary professional baseball player, Yogi Berra, once remarked “when you come to the fork in the road, take it.” Much like many other Yogiisms, the intent of the phrase was quite literal. It turns out that Yogi was giving directions to his home. He lived on a circular road whereby no matter what direction you chose when you reached the fork, you would end up at his residence. We think that we are at an analogous point for the bond market. All paths point to a bull market in the near future.

At Westshore, we tend to evaluate asset classes in terms of probability trees. Said differently, we consider all the predicted outcomes in response to a particular set of circumstances and select the “fork” that delivers the highest odds of reaching our desired investment destination. Our analysis leads us to believe that bonds have a virtuous path in all but a small minority of events. Let’s examine various paths forward. There are essentially three intertwined variables that determine the direction of fixed income investments. We need to evaluate the strength of the economy, the path of inflation, and the direction of interest rates. If we plot these variables on a continuum of hot, medium, and cold, we can start to assemble all possible outcomes. What we find is that bonds underperform when the economy and inflation remain hot, and interest rates go higher (inflationary environment), or in a very rare situation when the economy weakens while inflation and interest rates stay high (stagflation).

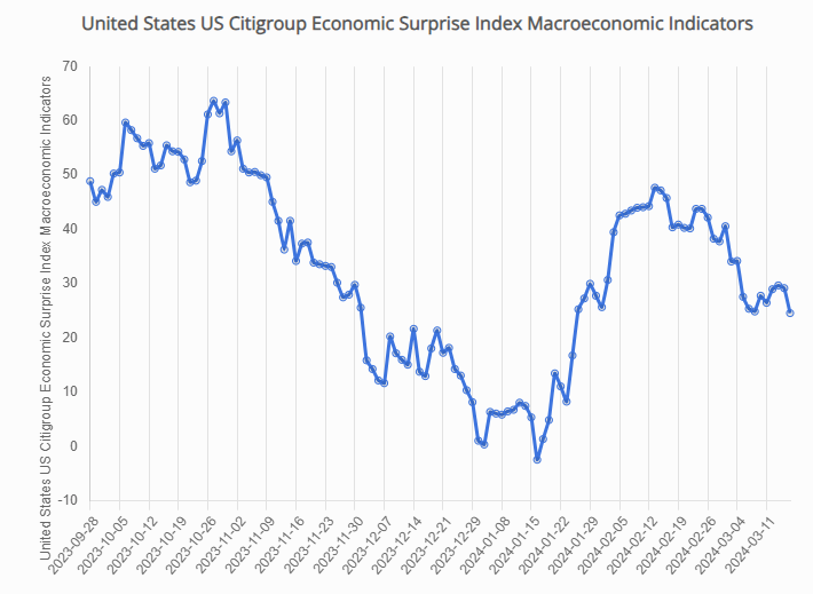

Where do we reside today? With regard to the US economy, if we look at the Citigroup Economic Surprise Index, a measure of differences between actual economic releases and consensus expectations, we find that the US economy is weakening.

Source: Citigroup

Of note, the two most reliable indicators, the ISM Manufacturing Index as well as the ISM Services Index, both fell marginally below 50 percent in the May reporting period, an indication that both engines of the US economy are stagnating (a reading below 50 indicates economic contraction while a reading above 50 indicates expansion). Meanwhile consumer sentiment measured by the US Conference Board deteriorated for the third consecutive month in April, falling to the lowest level since 2022. Consumers’ assessment of current business and labor market conditions declined as did the Expectations Index which fell into an area that often signals a forthcoming recession. While we discount an outright recession, given strong employment trends, we believe the signposts are ample that high interest rates are starting to cause the economy to slow. This is a positive outcome for bonds.

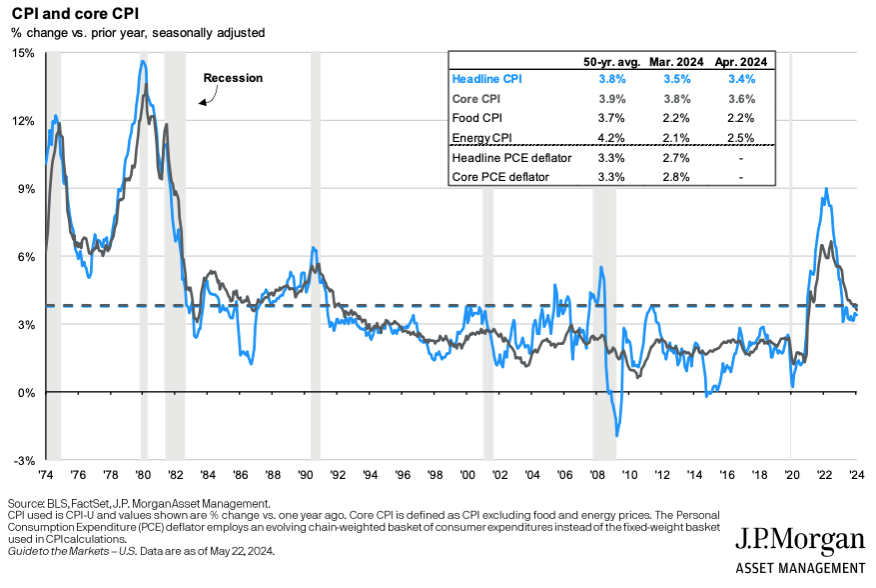

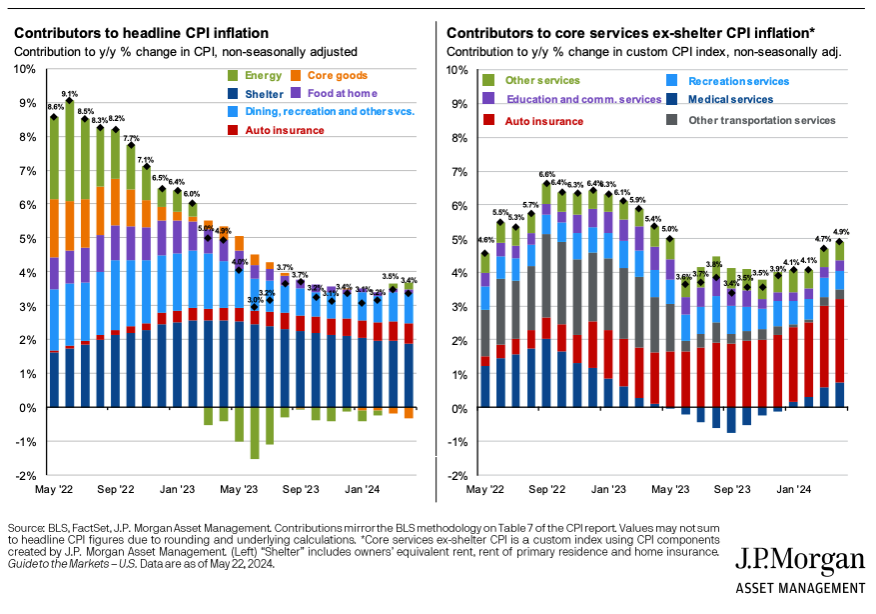

In the meantime, inflation is also moderating. While some have been disappointed in its persistence, it is hard to argue that the Federal Reserve hasn’t made substantial progress towards its 2% long term target. Inflation peaked in June 2022 at 9.1% according to the Consumer Price Index (CPI). We have since stabilized at 3.4% in recent months.

While this recent flatlining of CPI has been disconcerting to some, the majority of remaining inflation (roughly 75%) has to do with two culprits, namely shelter pricing (rents) and automobile insurance. While these are clearly large pieces of the inflation calculus, there are reasons for optimism. First, the Bureau of Labor Statistics uses historical, lagged data, in the shelter calculation (rent data flows in over 9 months in arrears) to smooth out natural volatility in the dataset. However, in this instance, it has backfired by painting an inaccurate representation. Real rental measures for housing (Apartments.com, Rent.com) show a considerable moderation over the past 9 months. That indicates relief is coming. Second, automobile insurance doesn’t reprice in real time either. Auto insurers must seek approval from state insurance regulators to raise prices. The pandemic caused car owners to drive quite a bit less. Miles driven fell and so did accident frequency. However, the reopening of the economy allowed people to get back to work, get back to school, go on driving vacations, and participate in lots of other activities. In other words, driving trends normalized. With more people on the road, accidents rose, as did loss experience for the insurers. Auto insurance providers are amidst repricing for these trends, and the fact that they require regulatory approval, strings out how we experience this inflationary event. That said, it will be transitory. Once they have repriced their book of business, they don’t need to do it again. Bottom line, we argue that inflation is at worst flatlining, and at best, tapering downward. It is not accelerating. Again, this is positive for bonds.

However, there continue to be doubters. A small minority of people have gravitated to a more severe scenario where the economy slows and yet inflation goes higher, an event called stagflation. We strongly disagree. It should be noted that the United States experienced stagflation in the 1970s. There are some parallels that invite the comparison, but there are also some very stark differences. The previous stagflation event coalesced around oil supply shocks that drove the price of energy to stratospheric highs. There was the Arab-Israel War in 1973-74 that caused OPEC to embargo oil headed for the United States in retaliation for the US arming Israel. We saw that once again when the US embargoed trade with Iran in response to the Iranian Hostage Crisis in 1979. It was further exacerbated during the Iran – Iraq war in early 1980, when 8% of the world’s oil output was shut in as war raged.

Many want to draw similarities between the 1970s-early 1980s period and present day. And to be clear, there are some resemblances. Russia, a major oil exporter, invaded Ukraine and the world largely responded by applying broad sanctions. Additionally, the Middle East is a hotbed of activity at present with Israel engaged in a battle with Hamas not only within in Gaza borders, but also hitting strategic targets in Syria, Jordan, and Iran. Finally, we have Houthi rebels within Yemen attempting to disrupt shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden that threatens oil and other export traffic. However, it is very important to note the differences between modern day and the 1970s. First, the US consumer spent nearly 8% of discretionary income on energy at the peak in the 1970s. That figure is under 3% today. Second, the US is energy independent today as opposed to the 1970s when we imported a significant amount of crude oil. Third, while sanctions have been applied to Russia, they continue to ship a record amount of oil. How? Instead of oil flowing to Europe and Japan, they are simply shipping their volumes to China and India who are more than willing to buy Russian crude oil at cheapened prices. Fourth, Israel and Gaza produce no meaningful volumes of crude oil. Their conflict has not disrupted supply. Fifth, despite fears that this conflict would evolve into a broader Middle Eastern war, that hasn’t happened. The dustup between Israel and Iran was quickly put to bed when each launched retaliatory strikes at tertiary targets that were designed to cause minimal damage, a clear indication that each party didn’t want to directly engage and risk instigating a bigger, broader conflict. Finally, the Houthi strikes have largely been put down by a strong world coalition that includes many oil-export-dependent Middle Eastern countries who need their oil to reach international destinations. But don’t take my word for it. Look no further than current oil prices. The NYMEX crude oil futures price has remained remarkably steady over the past two years.

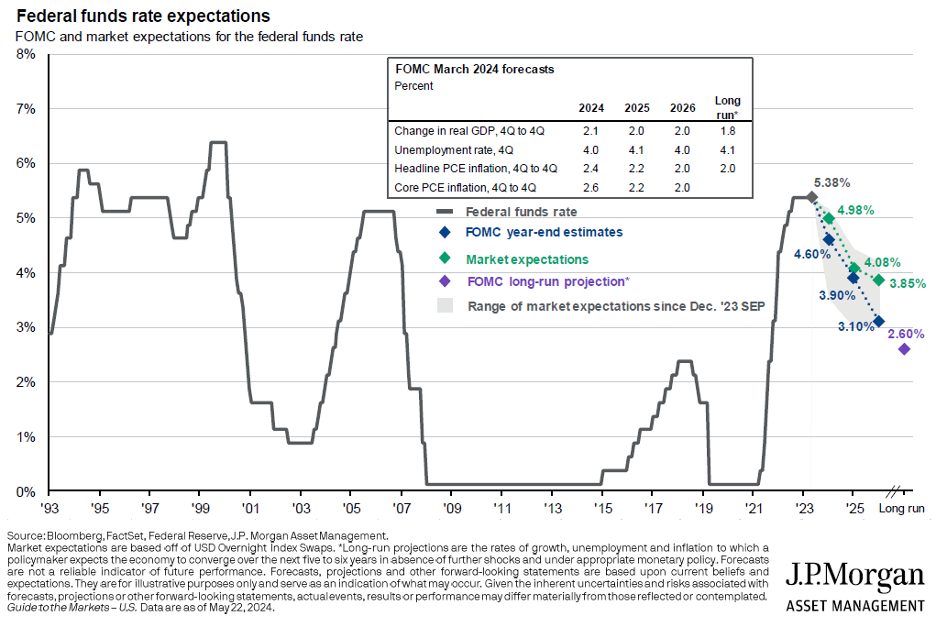

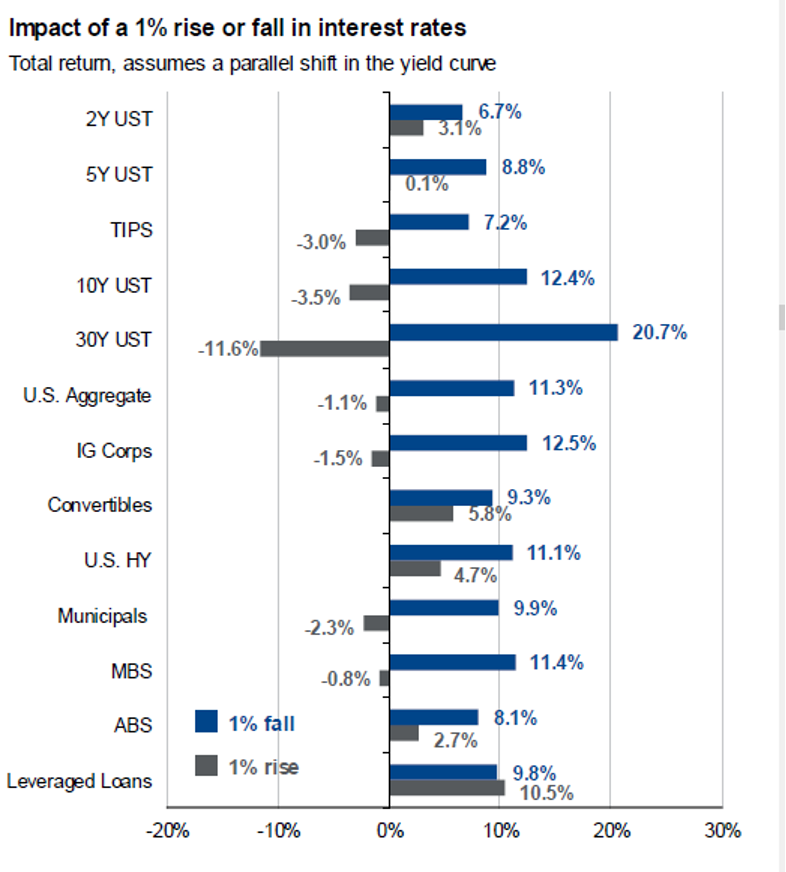

So, if we can rule out a strong economy leading to hot inflation and rising rates, as well as a stagflationary episode driven by an oil shock, what are the remaining probability tree considerations? We see three potential outcomes. The first involves a moderating economy with stagnant inflation. While not ideal, this is still fine for bonds. This scenario likely means that the Federal Reserve keeps interest rates higher for longer to combat inflation. While that prevents capital appreciation for bonds, it still allows investors to clip a very healthy coupon. Remember, bonds yields are at 15-year highs. By contrast, if the economy cools and inflation moderates, interest rates will fall and bonds will appreciate. Finally, if the economy falls prey to recession, inflation will likely decrement quickly, and interest rates will fall precipitously. In that case, bonds will rally substantially. The following chart illustrates how various bonds would fare in an environment where interest rates rise (grey line) or fall (blue line) by 1%. As you can see, the returns from here are asymmetric in favor of the investor. In other words, investors make more when interest rates fall than they would lose if interest rates rise. We love to bet on asymmetric payoff profiles.

Source: JP Morgan Asset Management

Source: JP Morgan Asset Management

As we evaluate the chess board, it simply seems to be a matter of time before interest rates head lower. The market is fixated on timing, ruminating over whether a cut will happen in June, July, or September (our bet is September for reference). We think that is missing the metaphorical forest for the trees. The key question is not when it happens, it is if it happens. We believe rate cuts will happen. And by the way, we aren’t out on a limb. The Federal Reserve makes public its own prediction for forward interest rates. As you can see with the blue diamonds below, the Fed sees rates heading significantly lower in future periods.

The triangulation of all this work leads us to the following conclusion. We think the outcomes that would pressure bonds, namely accelerating inflation or stagflation, are unlikely. By contrast, we believe the alternative paths, or forks in the road, all deliver us to our desired destination of better bond performance in varying degrees. Thus, we think it is an opportune moment to buy, buy, bonds. As always, we welcome your questions.